CHRIS ARMSTRONG August, 8,2011

Excerpt from C.S. Lewis's

Dark Night of the Soul

I’d suggest one good reason for giving the “dark night” a second look is a shocking fact about who undergoes it. It would be one thing if this experience enveloped only, say, backsliders or immature Christians or those involved in obvious sin. But with great regularity, we find the experience in the life stories of those we think of as having been especially faithful witnesses to the faith: People such as C. S. Lewis. Mother Teresa. Martin Luther. Each of these suffered particularly intense episodes of “dark night of the soul.” And perhaps the best way to begin to understand this experience for ourselves is to listen in on their struggles to find meaning in their darkness.

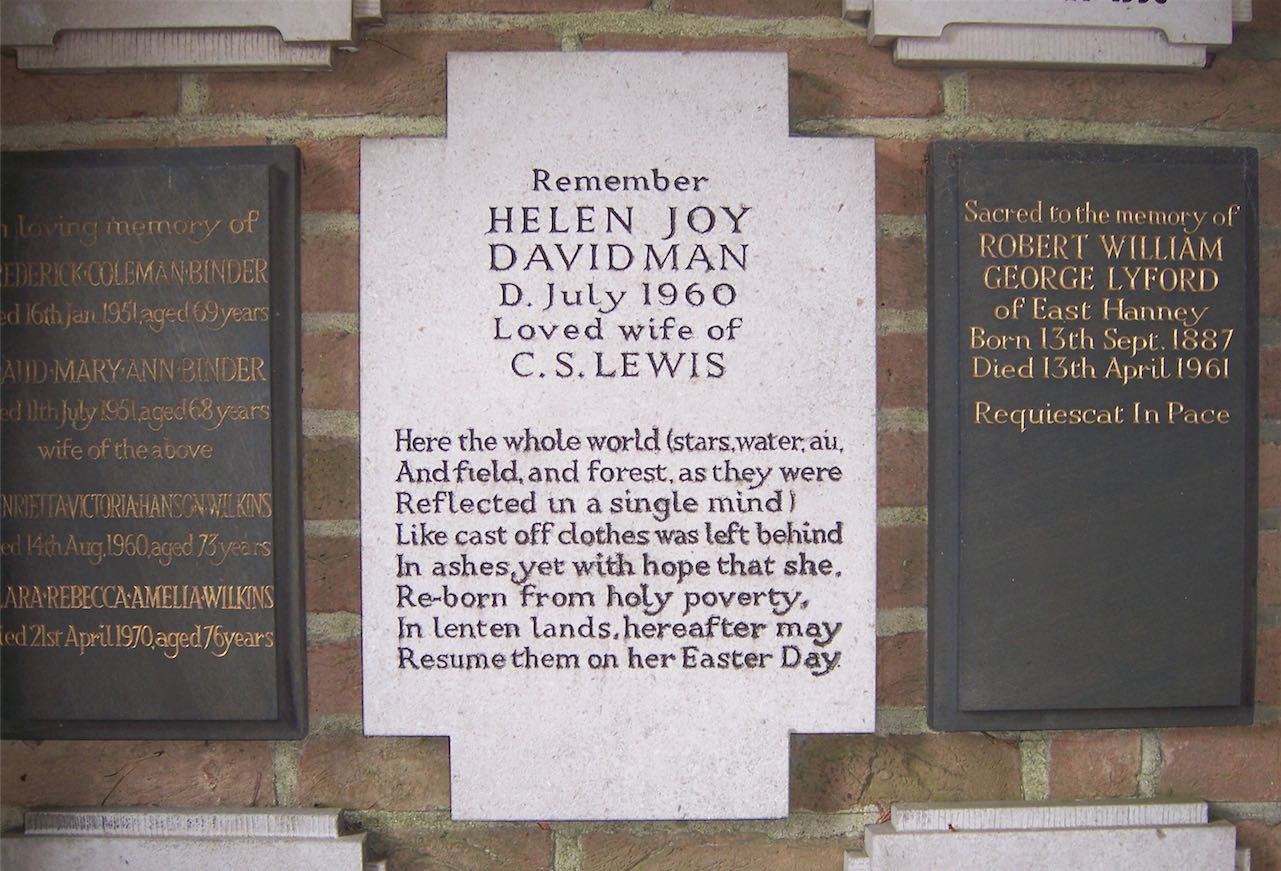

Lewis’s dark night came after the death of his wife Joy. Mother Teresa’s came at the very founding of her Missionaries of Charity and lasted to the end of her life, with little respite. Luther’s plagued him in one form as a young monk, and then in several others as a Reformer.

Of course, we could draw our own conclusions about why these saints have suffered thus — and historians have frequently done so. Perhaps some character flaw or pathology has led them away from the Divine Presence. The rational apologist Lewis, say some scholars, finally discovered after the death of his wife Joy that the God he had imagined was no longer a supportable hypothesis. The Absence he felt was in fact his coming to realization that Christianity was a fiction. Some critics have traced Mother Teresa’s “dark night” to an almost masochistic proclivity for pain, rooted in a certain Catholic understanding of suffering as inherently redemptive and spiritually meritorious. Most famously, Luther’s life story spawned in the 20th century a cottage industry of psycho-historical interpretation, led by Erik Erickson’s argument that a fraught relationship with his father created a cycle of overachievement and self-doubt that plunged the Reformer into the Anfechtungen — periods of depression and self-doubt — which never left him alone for long.

This sort of analysis opens up an even simpler explanation. Perhaps the Dark Night is nothing more than an artifact of depressive states of mind that have decidedly non-spiritual origins. So Luther’s many episodes of spiritual darkness (it is said) can be explained easily. Each one was preceded by, and triggered by, a physical illness. (The pinnacle of this sort of interpretation must surely be the book by German scholar Annemarie Halder that chronicled the Reformer’s bladder stones from 1536 to 1546, linking these painful occurrences to his Anfechtungen.)

Of course, the psychosomatic dimensions of illness do run both ways — from physical to psychological (and indeed, spiritual) as well as vice-versa. But such interpretations of the Dark Night remind one of Ebenezer Scrooge who, when confronted by the Ghost of Christmas Past, loudly insisted that the apparition was just a stomach disorder, a mere trick of the psyche resulting from “an undigested bit of beef...a fragment of an underdone potato.” Certainly in the opinions of Lewis, Teresa, and Luther, something more was at work in their darkness:

It was in 1956, in his late 50s, that C. S. Lewis finally found love. He married the object of his affections, American writer Joy Gresham; but four years later, after an agonizing battle, Joy died of cancer. During the period of intense grieving that followed, Lewis filled four notebooks — first, with words of anguish and rage, then increasingly with an introspective record of the changes that this loss worked in his character. The notebooks were published one year after Joy’s death as A Grief Observed, under the pseudonym N. W. Clerk.

You can read the full article, "C S Lewis’s Dark Night of the Soul," on Chris Armstrong's website.

Chris Armstrong August 24, 2011

An Excerpt from Martin Luther’s

Anfechtungen

Historian David Steinmetz describes the terror which Luther experienced at these times as a fear that “God had turned his back on him once and for all,” abandoning him “to suffer the pains of hell.” Feeling “alone in the universe,” Luther “doubted his own faith, his own mission, and the goodness of God—doubts which, because they verged on blasphemy, drove him deeper and deeper” into despair. His prayers met a “wall of indifferent silence.” He experienced heart palpitations, crying spells and profuse sweating. He was convinced that he would die soon and go straight to hell. “For more than a week I was close to the gates of death and hell. I trembled in all my members. Christ was wholly lost. I was shaken by desperation and blasphemy of God.’” His faith was as if it had never been. He “despised himself and murmured against God.” Indeed, his friend Philip Melanchthon said that the terrors afflicting Luther became so severe that he almost died. The term “spiritual warfare” seems apt.

These times of Anfechtungen (to use his term for it) drove Luther back to Scripture and to the sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist. Another valuable medicine in the struggle for L was “the fellowship of the church: “No one should be alone when he opposes Satan. The church and the ministry of the Word were instituted for this purpose, that hands may be joined together and one may help another. If the prayer of one doesn’t help, the prayer of another will.”

You can read the full article, "Martin Luther’s Anfechtungen," on Chris Armstrong's website.

CHRIS ARMSTRONG August 24, 2011

An Excerpt from

Mother Teresa's

Long Dark Night

Almost every Christian thinker who has commented on the experience of divine absence and spiritual desolation called by John of the Cross “the Dark Night of the Soul” has concluded that the experience must have some spiritual usefulness. That’s one of the things that shocked the world when, in 2007, we discovered through a posthumously published book that Mother Teresa of Calcutta had undergone a severe, intense dark night that persisted through almost her entire ministry life, right up until her death.:

It didn’t seem to make sense. Here was a person who, if anyone could merit the title during her lifetime, was thought of by almost everyone who knew of her as an exemplary saint. With our theology of a relational God, we would expect Him to smile benevolently down on such a person, even previewing some of his “Well done, good and faithful servant” in His behavior toward her in this life. And yet here it was, this agonizing decades-long Absence that darkened her whole life and left her only briefly, on one occasion.:

What on earth sort of usefulness could such dereliction have for a person such as Mother Teresa? The editor of her letters makes it clear that it was not a “thorn” to rescue her from some sort of overweening pride — she had begun the ministry of the Missionaries of Charity based on a youthful vow that she would do everything God asked, submitting herself absolutely to His will. She was little inclined to pride, as all around her testified.

Please click on this link to read the full article.

You can read the full article, "Mother Teresa’s Long Dark Night", on Chris Armstrong's website.

Chris Armstrong directs Opus: The Art of Work at Wheaton College, where he also serves on the biblical and theological studies faculty. He has written Patron Saints for Postmoderns (IVP, 2009) and the forthcoming Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians: Finding Authentic Faith in a Forgotten Age with C. S. Lewis (Baker Academic). He is senior editor of Christian History magazine and founding senior editor of the Patheos Faith and Work channel. He blogs at gratefultothedead.wordpress.com.

Permission to use excerpts from his articles was given by the author.

"Inside she was feeling a terrible emptiness... She felt alone, isolated. The longing in her was so strong, it felt to her like torture. The darkness she lived with was an essential element of who she was and her letters document what she went through...If these letters were to be made public, then way one who went through similar trials would benefit from them... During her life she became an icon of compassion to people of all faiths."

Photo of Joy's tomb by Dave, Creative Commons

Photo of Wartburg Castle, where Martin Luther stayed from May 1521 until March 1522, by Tjflex2, Creative Commons

Photo of Mother Teresa by Fred Miller